Let’s delve into JSON Web Tokens, their history, and the problems they solve. We’ll discuss the importance of thorough validation, as some developers tend to overlook this aspect. Additionally, we’ll cover Bearer Tokens, their issues, and possible remedies. Common mistakes made with JSON Web Tokens will also be addressed, followed by an exploration of Refresh Tokens – a related, yet distinct, concept. Lastly, we’ll touch upon JSON Web Token revocation. So, let’s dive in.

This article is based upon a presentation from Dan Moore of FusionAuth.

What are JWTs?

JSON Web Token, or JWT (pronounced “jawt” as per the specifications), is a widely recognized standard in the tech industry.

JSON Web Tokens (JWT) belong to a family of specifications around RFC 7519, which include RFC 7516, 7517, 7518, 7520, and others. These standards, developed by the IETF, focus on various aspects of tokens, signing, and encryption. So, when discussing JWTs, it’s essential to remember that they are part of a broader set of related standards.

JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) first appeared around 2015-2017 and can be either signed or encrypted. A signed JWT ensures the integrity of the token, meaning you can confirm it hasn’t been altered, but its contents are not secret. It’s crucial not to include sensitive information like social security numbers in signed JWTs. On the other hand, encrypted JWTs keep the payload secret, as the name suggests. Understanding the difference between signed and encrypted JWTs is essential when working with these tokens.

While signed JWTs are more common, it’s important to note that their contents are not secret, and sensitive information should never be included in them. If a signed JWT contains a secret, you should either convert it to an encrypted JWT or find a way to exclude the secret, as anyone who obtains the JWT can view that secret. Encrypted JWTs, on the other hand, keep the payload secret, ensuring the information remains confidential.

JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) are frequently used as stateless, portable tokens of identity. They are considered stateless because their authenticity and integrity can be verified without needing to communicate with a server to confirm their validity. This feature allows them to function independently, without constant server-side validation. JWTs are also portable due to their compatibility with HTTP, easily fitting into form parameters and headers.

JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) can be stored in cookies and are often used as tokens of identity at the end of an authentication event, representing the user. For example, this is how FusionAuth utilizes them. The holder of the token is usually the person who authenticated, although there are some caveats to this. JWTs are particularly useful for APIs and microservices, as you can generate a JWT in one location, pass it to a client, and then have the client present it to various APIs or microservices to access data or functionality on behalf of that user. This makes JWTs ideal for distributed systems where stateless, portable identity representation is essential.

JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) are widely used by various identity providers, including FusionAuth, Auth0, Firebase, and Cognito. These providers produce JWTs to grant access to specific functionalities for users holding the tokens. APIs and microservices can validate JWTs, ensuring that the access is provided to the intended users. This widespread support and adoption of JWTs across the industry reinforces their importance as a standard in stateless, portable identity representation.

Leveraging JSON Web Tokens in a Complex To-Do Application

JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) have gained widespread popularity, not only because they are supported by various identity providers, but also due to extensive documentation, library support, and general understanding within the tech industry. JWTs have been around for a while, and their primary purpose is to address the critical issue of distributed identity, making them an invaluable tool in modern applications.

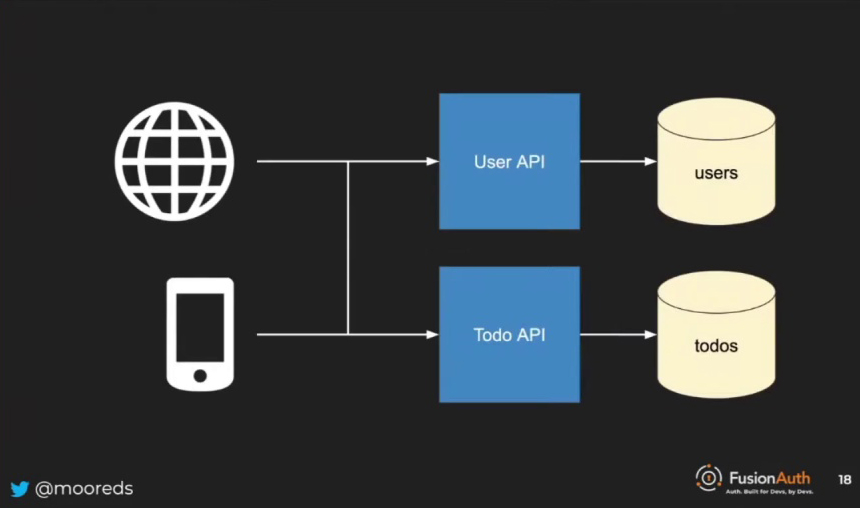

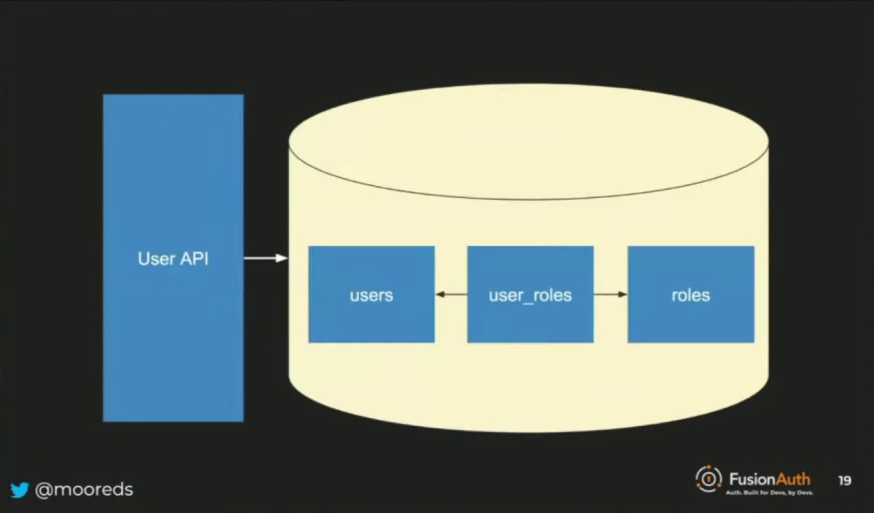

In our example, we have a typical, slightly over-engineered to-do application. The architecture consists of clients on the left side, which could be browsers, native clients, or other types of clients. These clients communicate with various APIs, which in turn interact with a data store. The data store for the user API has a standard structure, containing users, roles, and a mapping between them. Meanwhile, the to-do API data store consists of a single table for to-dos. This table has some interesting features, demonstrating the complexity that can arise even in a simple to-do application.

The data store for the user API houses users, roles, and their mappings, while the to-do API data store contains a single table for to-dos with fields like text, status, and user ID. Notably, even in a simple to-do application, complexity can arise due to the distributed nature of the system. For instance, the user ID field cannot be a foreign key, as cross-database references are not supported. Although the user ID is always present and set to not null, it cannot reference the user table directly.

CREATE TABLE todos {

id INT NOT NULL,

text TEXT NOT NULL,

status INT NOT NULL,

user_id CHAR(40) NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (id)

);

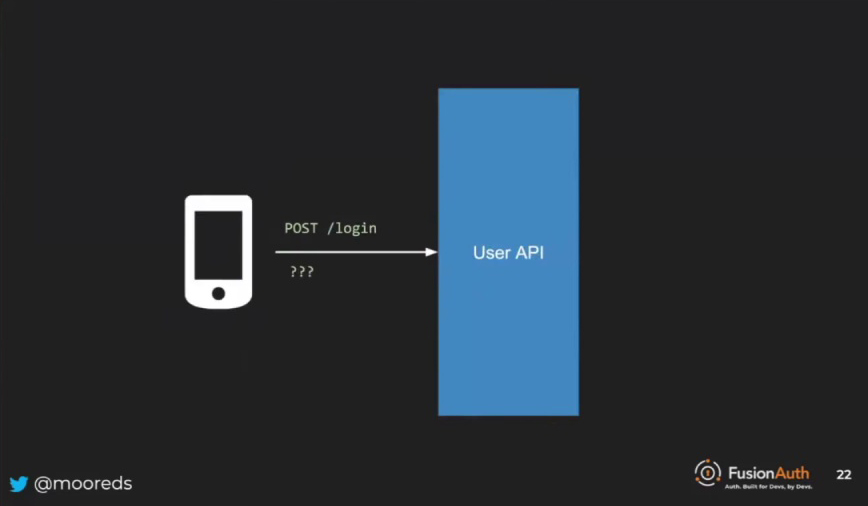

In the over-engineered to-do application, accessing to-dos requires an authentication process. First, the user provides their credentials, such as a username and password, by posting the information to the user API. This authentication step is essential for ensuring secure access to the to-dos and maintaining the integrity of the system.

Securing User Data and To-dos: Opaque Tokens, Validation, and Architectural Considerations

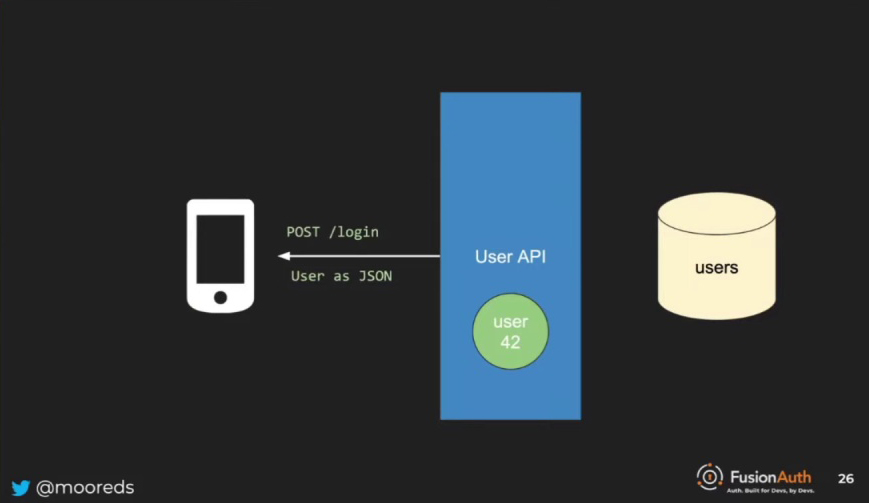

In the over-engineered to-do application, linking the to-dos back to the user after the login event is crucial. During the login process, the user API communicates with the user database and retrieves the user’s data. This user data plays a vital role in connecting the to-dos to the user, ensuring secure access and maintaining the integrity of the system.

In the case of JSON Web Tokens for developers, the details of the authentication process are not crucial. What matters is that at the end of the process, the developer receives a user object, usually in JSON format for modern web applications. The user object typically contains information such as an identifier, name, roles, and email, among other details. This user data is passed to the client and plays a vital role in connecting the user with their to-dos, ensuring secure access, and maintaining the integrity of the system.

{

"user": {

"id": "42",

"name": "Dan Moore",

"email": "dan@fusionauth.io",

"roles": ["admin"]

}

}

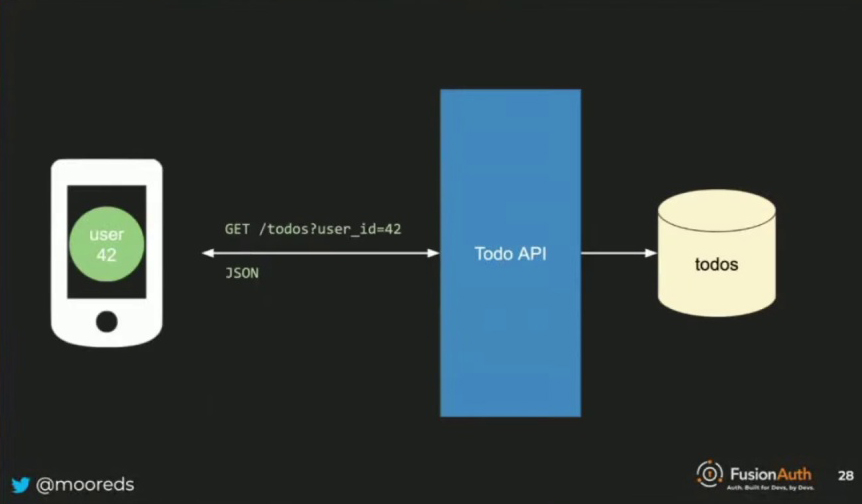

In the over-engineered to-do application, when the client wants to get the to-dos for user ID 42, they pass that identifier to the to-do API. The API then queries the to-dos database and finds that Dan has 25 different to-dos. It wraps them up as JSON and sends them back to the client, which then renders them. However, this approach is not ideal because you cannot trust the client to maintain the integrity of the system.

However, a potential security issue arises from the client directly requesting to-dos using the user ID. Attackers could inspect the client code or network traffic to identify that user ID 42 is being used, giving them insight into the number of users in the system and allowing them to iterate through user IDs to access other users’ to-dos. To prevent this, the to-do API must not accept user IDs blindly and needs a mechanism to protect user privacy. One potential solution is using an opaque token approach.

In this scenario, the user API generates a long random string, known as an opaque token, along with the user data. The client is coded to present this token to the to-do API, rather than the user ID. While this approach addresses the issue of revealing the number of users in the system, it still leaves room for enumeration attacks. Attackers could potentially rent multiple EC2 instances on AWS and iterate through every possible token value to scrape all the to-dos. To prevent this, the to-do API cannot use the opaque token as an identifier in the to-dos database. Instead, it must present this token to the user API for validation.

The user API validates the opaque token by checking its database, as it generated the token initially. If the token is valid, the user API returns the user ID or the entire user object, allowing the to-do API to retrieve the to-dos. If the token is not valid, the user API sends an error code, indicating that an issue occurred, such as a bug or an attempt at privilege escalation, and the to-do API should not return the to-dos. This approach is valid, but like any engineering issue, there are trade-offs to consider.

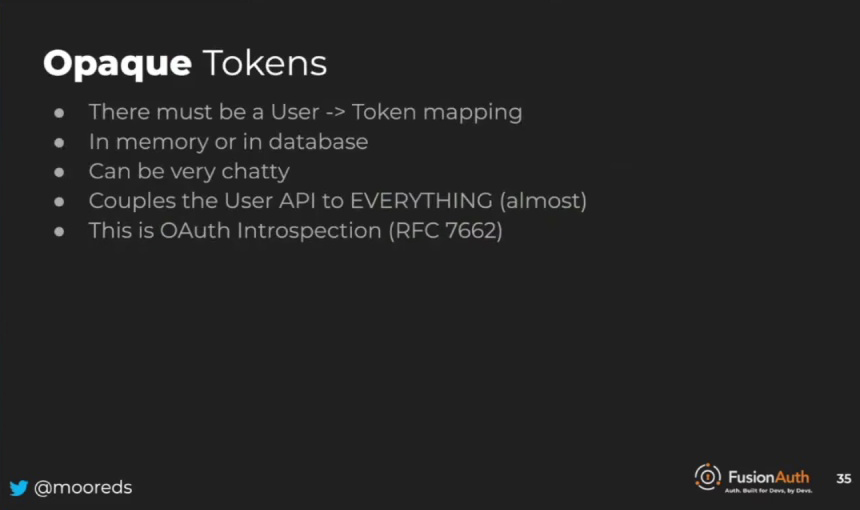

Maintaining a user token mapping at the user API can range from trivial to a significant challenge, depending on the number of users. This approach can also be quite chatty, as the to-do API needs to present the token to the user API every time it receives a request, unless caching is implemented, which introduces additional complexities. Architecturally, this method heavily couples the user API to almost everything. Whenever requests come in from any user-related APIs, the token must be extracted and presented to the user API. Although this might work for systems with only a few APIs, it may become problematic as the number of APIs increases.

With a growing number of APIs, scaling the user API becomes increasingly necessary. This flow is similar to OAuth introspection, an IETF-approved RFC for determining the validity of client requests. It’s worth noting that this process is not exactly OAuth introspection, but shares similarities with it. Understanding these patterns and trade-offs is crucial for managing complex systems and ensuring secure access to user information.

Leveraging JWTs for Simplified Authentication in Complex Systems

In the over-engineered to-do application, JWTs offer an alternative solution to the opaque token approach. The user API generates a JWT, which is then passed to the client. The client can extract the JWT and present it to the to-do API, allowing the to-do API to verify the signer, validity, recipient, and other attributes without needing to communicate with the user API. This approach simplifies the authentication process and reduces the coupling between the user API and other APIs, making it easier to manage in complex systems.

A JWT can be signed using a public-private key pair or a symmetric key, which will be discussed in more detail later. The main advantage is that the to-do API doesn’t need to communicate with the user API, as the token’s signature guarantees its correctness. Additionally, a JWT can hold various information, such as roles, subscription statuses, or plan details. However, it’s important to note that the content of a JWT is visible to anyone who obtains it, so sensitive information should be avoided. Now, let’s examine what a signed JSON Web Token looks like.

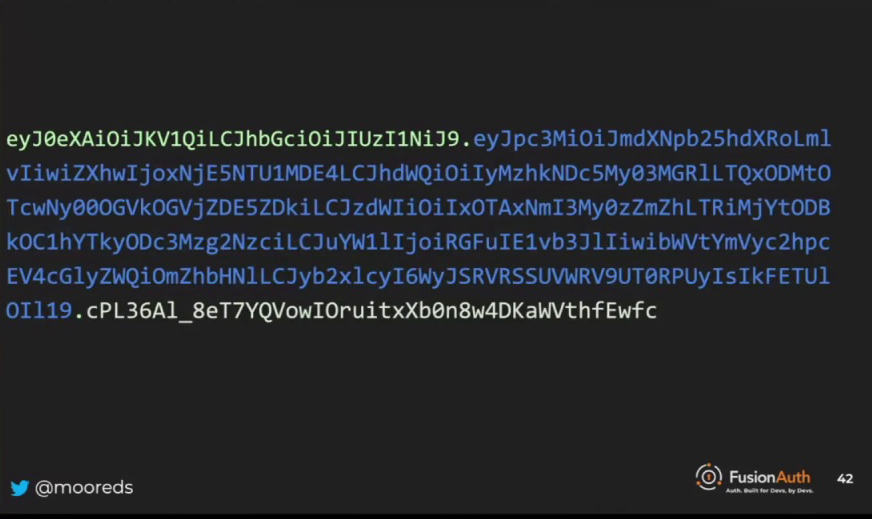

In the over-engineered to-do application, a signed JSON Web Token (JWT) consists of three parts: the header (green), the payload or body (blue), and the signature (white or tan). Both the header and the payload are Base64 URL encoded strings.

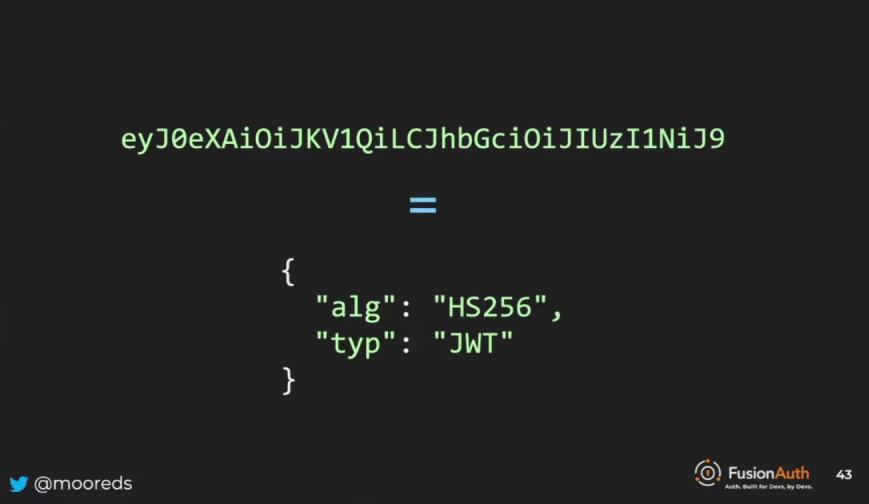

That’s why you’ll often see JWTs starting with “EYJ0”, as it represents the URL-encoded string for “{” (curly brace). If you want to decode the Base64 URL encoded strings in a JWT, you can simply search for a Base64 decoder online, and it will work most of the time.

Understanding JWT Structure and Validation: Headers, Claims and Signatures

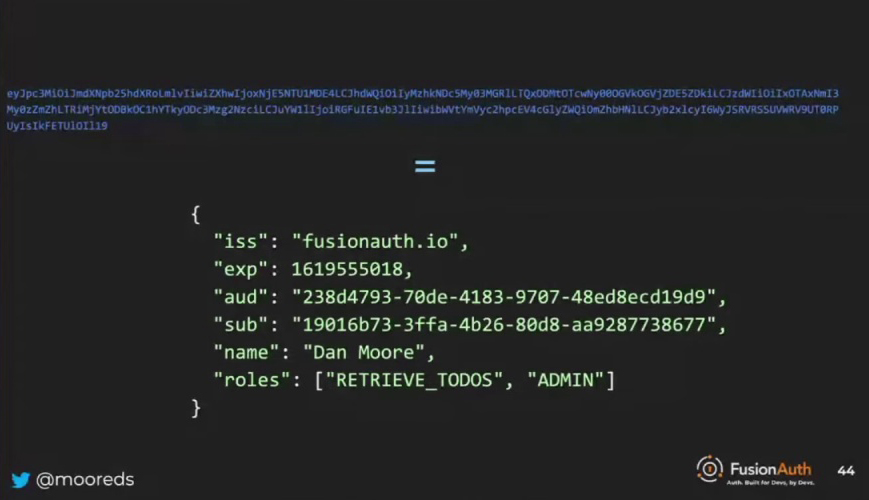

In a signed JSON Web Token (JWT), the header contains metadata, such as the algorithm used to sign it, the type of JWT, and sometimes a key identifier to determine which key was used for signing. The body, where things get interesting, can store any information as it is a JSON object. The keys of the JSON object are called claims, which provide details about the user. Some claims, like issuer, expiration, audience, and subject, are standardized, while others are not.

In a JWT, you can store a variety of data types, such as arrays, arrays of arrays, or arrays of objects of arrays. There’s no specific limit on the JWT length, but the transport layer might impose a limit. For example, if you pass a JWT as a header, some browsers might have a maximum header length, which would effectively limit the JWT size. The flexibility of JWTs allows for the inclusion of non-standardized information, like names and roles, to be helpful to downstream JWT consumers like the to-do API.

In a JWT, the signature is an essential component, ensuring the integrity and authenticity of the token. Although you will most likely use a library to generate the signature, understanding its function is valuable. The process involves performing a cryptographic operation on the header and payload, followed by Base64 URL encoding the result. When passing a JWT as a cookie, you may be limited by the cookie size, requiring you to break it apart and reassemble it if necessary. Overall, the signature plays a crucial role in maintaining the security of JWTs.

The type of cryptographic operation performed on a JWT depends on the chosen algorithm, which can be symmetric or asymmetric. Libraries are typically used to handle these operations, but it’s essential to understand that the signature is tied to the header and the body. If any alterations are made to the header or body, such as changing a role, the signature will no longer match. This leads to the process of JSON Web Token validation, which involves the necessary steps developers need to take when receiving a JWT to ensure its integrity and authenticity.

Securing User Data with JWT Validation

APIs like the to-do API receive JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) from the client to protect user data, such as personal to-dos. To ensure that only authorized users can access their to-dos, it is crucial to validate the JWT. The first step in this process is validating the signature. It is recommended to use a library for this task, as most programming languages have a dedicated JWT library available. By effectively validating the JWT, you can maintain the security and integrity of user data within the to-do application.

When working with JSON Web Tokens (JWTs), it’s important to use a trustworthy library, preferably an open-source one, for validating the tokens. When using a library to check the JWT, if it returns an exception or error indicating that the signature doesn’t match, the process should be stopped immediately. This error could result from a bug, privilege escalation, or other issues, but it signifies that the JWT is not valid for further processing.

After validating the signature, it’s essential to validate the claims within the JWT. This is a step that some developers may overlook, but it is crucial for maintaining the security and integrity of user data within applications like the to-do API.

After checking the JWT signature, you must validate the values of the JSON object keys, which can be considered business logic. While some libraries can help with certain claims, you’ll need to handle custom claims like checking for a paid user. This means you need to write the logic for verifying these custom attributes. Although you have to write this logic, you can create a custom library or module to avoid writing it for each individual API. This will ensure the security and integrity of user data within applications like the to-do API.

In a JWT, both standardized and custom claims exist. For example, the issuer claim verifies that the JWT was created by the expected entity, like the user API in a to-do application. It’s essential to check the issuer to ensure the JWT is generated by the correct party. Another claim to validate is the expiration time, which is the number of seconds since the Unix epoch. If the expiration time is in the future, the JWT is most likely valid. Validating these claims helps maintain the security and integrity of the user data within applications.

In a JWT, it’s crucial to validate claims like expiration time and audience. If the expiration time is in the past, the JWT is invalid, and processing should stop, just as if the signature validation failed. The audience claim indicates the intended recipient of the JWT. In the given scenario, the to-do API is the intended recipient. If the audience claim doesn’t match the expected value, processing should be halted. This is important because there could be multiple APIs with different user roles, and validating the audience ensures that the JWT is being used for the correct API.

{

"iss": "fusionauth.io",

"exp": 1619555018,

"aud": "238d4793-70de-4183-9707-48ed8ecd19d9",

"sub": "19016b73-3ffa-4b26-80d8-aa9287738677",

"name": "Dan Moore",

"roles": ["RETRIEVE_TODOS", "ADMIN"]

}

When dealing with JWTs in applications, it is essential to ensure the proper access level is granted, depending on the user’s role in various APIs. For example, an admin in the todo API might have access to view other users’ to-dos, while an admin in the accounting API may have the ability to send out checks. It is crucial that a JWT created for the to-do API is not presented to the accounting API, as it could lead to unauthorized access. To handle this, you can implement validation code which outlines a simple validation scenario to maintain the security and integrity of user data across different APIs.

// the todo api

const options = {

algorithms: "HS256",

ignoreExpiration: false,

issuer: "fusionauth.io"

}

const verified = jwt.verify(token, hmac_key, options);

// addl verification checks

if (verified.aud != 'myapp.example.com') {

throw "invalid audience";

}

if (!verified.premiumUser) {

throw "invalid access";

}

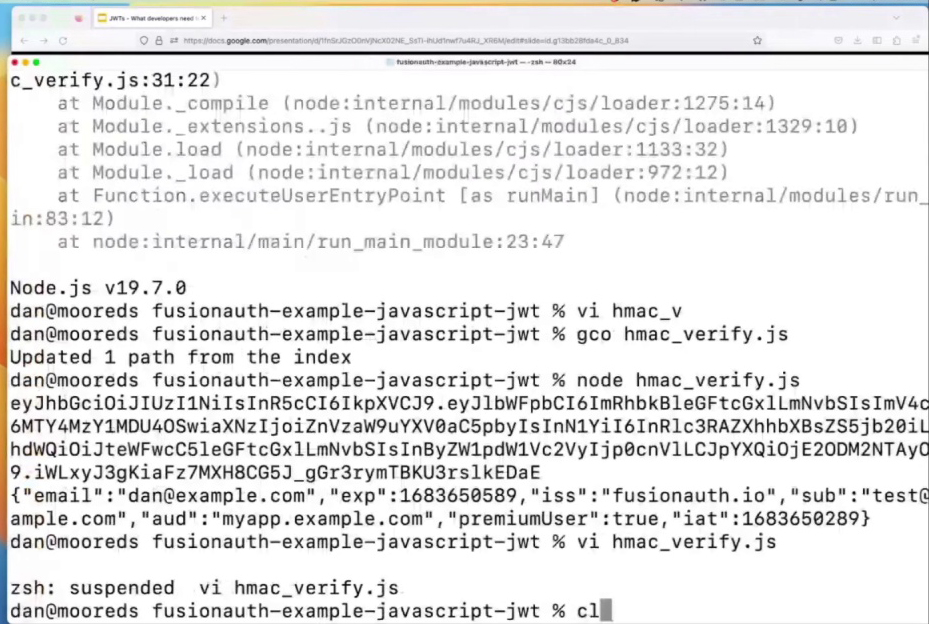

In the given example, if the HMAC key is changed, it demonstrates what happens when the signatures of JWTs don’t match. By creating a new HMAC key (const new HMAC key), the signature will be different, as the time has changed. This mismatch in signatures helps illustrate the importance of validating JWTs to ensure the security and integrity of user data within applications like the to-do API. When signatures don’t match, it’s crucial to halt further processing and investigate potential issues.

Securing User Data: The Importance of Bearer Token Security

We’ve examined the architectural benefits of using JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) and learned about their structure. We’ve also discussed the importance of validating JWTs to ensure the security and integrity of user data in applications like the to-do API. Now, let’s shift our focus to bearer tokens in general, which are closely related to JWTs. Bearer tokens are authentication tokens that grant access to resources on behalf of the bearer or holder, making them a convenient method for authorizing users in various scenarios.

Bearer tokens are a broader concept than JSON Web Tokens (JWTs), as JWTs are often used as bearer tokens, but bearer tokens can exist independently of JWTs. The main idea behind a bearer token is that possession of the token serves as proof of access. A helpful analogy to understand this concept is a car key – possessing the key grants access to the car.

If you have a simple car key without a biometric sensor, anyone holding the key can access and drive the car. Therefore, you must be cautious about the key’s location, as leaving it unattended could allow unauthorized individuals to take the car. Similarly, in the world of JWTs, you need to safeguard the JWT issued by the user API. If a malicious actor acquires the JWT, they can present it to the JWT API and potentially gain unauthorized access.

The JWT API will consider a stolen JWT as valid because the malicious actor didn’t create a new JWT but instead used an existing one. This can lead to unauthorized access to user data, making it essential to be cautious about storing and transmitting tokens. Protecting tokens during transit is crucial, and HTTPS serves as the gold standard for ensuring secure communication.

Securing JWTs: Common Issues

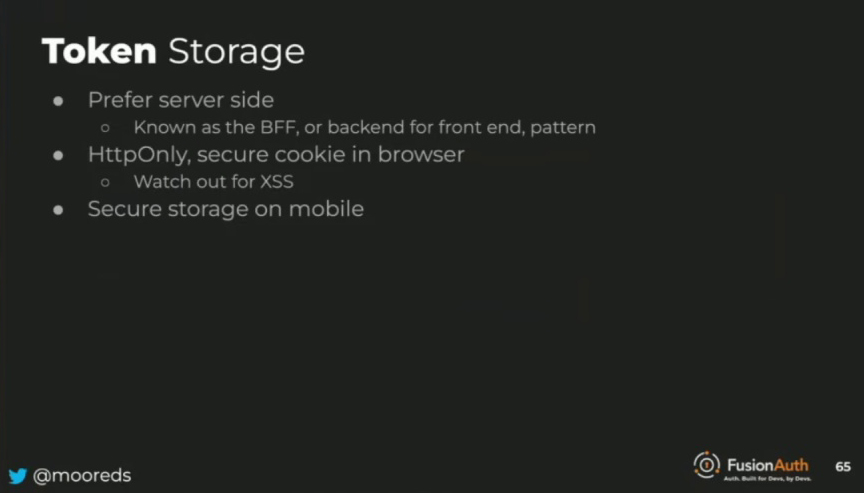

Avoid placing sensitive JWTs in URLs, as they may be cached as query parameters. For token storage, server-side storage is generally recommended, although use cases may vary. If a browser is used as a client, store JWTs as HtttpOnly secure cookies to eliminate cross-site scripting issues. For native clients, use secure storage options like keychains or Android’s secure storage.

You should also be aware that a JSON Web Token (JWT) can leak information even if you don’t store secrets in it. For example, if the audience claim is a number instead of a UUID, it may reveal the number of users in the system. Since JWTs are not secret, using a number like 42 for the audience ID or subject claim could inadvertently disclose that there are at least 42 users. To avoid this, use UUIDs for such claims. Additionally, when using symmetric key signing, like HMAC, the secret is shared between the entity signing the JWT and the entity verifying it, so take extra care to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of shared secrets.

It is possible to brute force a JSON Web Token (JWT) secret simply by using the token itself. This involves trying different secrets and running the cryptographic algorithm on the header and body, checking if the signature matches. This process continues with various secrets until a match is found. A GitHub project demonstrates this technique in C. The time taken to brute force the secret depends on the HMAC key length; shorter keys are quicker to crack, while longer keys take more time. This highlights the importance of avoiding the “none” algorithm for signing headers, as it leaves JWTs without any signature, making them vulnerable to exploitation.

Essentially, when there is no integrity check, anyone who discovers an API that accepts a JWT with no algorithm or signature can create any payload they want, base64 encode it, and present it to the API. This results in a completely valid JWT, emphasizing the importance of having proper checks in place to maintain the security and integrity of user data within applications.

Enhancing Security and Integrity of JWTs with Asymmetric Key Pairs

When dealing with JWTs, it’s crucial to avoid using the “none” algorithm, as it’s like accepting unsanitized user input – but worse. This is because unsanitized credentials might lead to unauthorized access, compromising the security and integrity of user data within applications. To further enhance security, it’s important to understand the differences between asymmetric and symmetric key pairs. Asymmetric key pairs involve a public and private key, while symmetric key pairs use a shared secret for both signing and verifying JWTs. Knowing the appropriate key pair type for your scenario can help maintain the confidentiality and integrity of your JWTs.

In our example, the user API generates a JSON Web Token (JWT) and passes it to the client, which then presents it to the to-do API. As previously mentioned, HMAC is a common algorithm used for this purpose, which means that both the user API and the to-do API share a secret. This shared secret is essential for maintaining the security and integrity of user data across different APIs.

Bearer tokens, such as JSON Web Tokens (JWTs), need to be protected and securely stored. When using symmetric key signing, like HMAC, sharing and distributing the secret securely is crucial. One option is to distribute multiple secrets during deployment for rotation purposes. However, asymmetric key pairs can help avoid this complexity. Asymmetric key pairs, like RSA or elliptic curve cryptography, use a private key to sign the JWT and a public key to verify it. This approach simplifies the distribution and management of keys, enhancing the security and integrity of user data across different APIs.

Using asymmetric key pairs can significantly improve scalability in various situations. For instance, sharing a secret between a small development team maintaining two or three APIs might not be a big issue. However, if you have two different companies or departments, sharing a secret becomes a much more significant concern. In our example, let’s say Pied Piper owns the user API, and Hooli owns the JWT API. Using asymmetric key pairs in such a scenario simplifies the distribution and management of keys, ultimately enhancing the security and integrity of user data across different APIs.

The user API generates a JWT, signs it with a private key, and passes it to the client. The client then presents the JWT to the JWT API, which can obtain the public key (since it’s public) and verify the JWT. This approach allows for scaling out to include other organizations. Security is also a crucial factor. When using a symmetric key pair, the same secret is used to sign and verify the JWT. This increases the attack surface, as every entity verifying a JWT needs to be as secure as the user API. Using asymmetric key pairs, like RSA or elliptic curve cryptography, can help mitigate this issue and maintain the security and integrity of user data across different APIs.

When using symmetric key signing like HMAC for JWTs, the security implications are significant. If someone steals the shared secret, they can create JWTs with any desired access, such as super admin privileges, until the secret is rotated. This poses a substantial risk to user data and API security. However, asymmetric key pairs for JWTs are between three and 10 times slower than symmetric key signing. If you’re processing a large number of JWTs, the trade-off between security and performance might be worth considering.

The Importance of Refresh Tokens

Refresh tokens are essential because access tokens, especially for users, are meant to be short-lived, lasting only seconds or minutes. In contrast, refresh tokens can be long-lived. They are presented to the user API, which then generates new JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) as needed. This helps maintain the security and integrity of user data within applications.

Refresh tokens play a crucial role in maintaining a balance between security and user experience. Without them, you’d have two undesirable alternatives. One is having short-lived access tokens, like five minutes, which would force users to log in frequently, leading to a poor user experience. The other option is having long-lived tokens, such as a month, which compromises security. Refresh tokens help avoid these issues by allowing users to obtain new JWTs without constantly logging in, ensuring a more seamless and secure experience.

Balancing Security and User Experience with Refresh Tokens in JWT-Based Systems

If someone manages to steal a JSON Web Token (JWT), they would have an extended period to exploit the token, pulling down data and potentially causing harm. This is why it’s essential to strike a balance between security and user experience using refresh tokens, which allow users to obtain new JWTs without logging in frequently. This approach ensures a more seamless and secure experience, minimizing the risk of unauthorized access and protecting user data.

Refresh tokens operate by being requested during the authentication process and being sent along with the JWT. The JWT is then presented to the API, and data is exchanged. This pattern continues throughout the JWT’s lifetime.

Eventually, the JSON Web Token (JWT) will expire, and the two APIs will deny further access to the user’s to-dos. At this point, the client can present the refresh token to the user API. The user API checks if the user is still valid, logged in, and has paid their bill, then issues a new JWT. The new JWT is sent to the client, which can then present it to the to-do API for validation. This process allows for re-authentication of the user in a silent manner, ensuring a seamless and secure experience.

In a JSON Web Token (JWT)-based system, revoking access during logout is primarily done by revoking the refresh token. When a user chooses to log out, the client sends a message to the user API to stop issuing JWTs for the associated refresh token and then deletes them from its storage. However, revoking the JWT itself is more complex, and there isn’t a straightforward method. RFC 7009 provides a way to revoke refresh tokens, but using this specification could result in losing certain capabilities.

Removing a public key from the list of public keys is one way to revoke access, as the library won’t be able to find the valid public key, resulting in a failed signature check. Another option is using very short lifetimes for JWTs, making them almost one-time use. A third option is employing a deny list, which is a FusionAuth-specific feature, but similar implementations exist in other libraries. When a user logs out, an event is triggered and sent to different APIs, notifying them that a specific refresh token has been revoked. This helps maintain security and integrity across various APIs.

Conclusion

JWTs serve as a valuable tool in the architectural tool belt, offering both advantages and disadvantages. While they can be used alongside web sessions, web sessions come with their own set of costs and benefits, such as using cookies and being less scalable. Despite these limitations, web sessions are simpler to understand. JWTs are not a one-size-fits-all solution, but they provide a powerful option for maintaining security and user experience across various APIs.

Additional resources, such as the JWT debugger and sample code, can help deepen your understanding of JSON Web Tokens. In-depth articles are available for further reading, providing comprehensive insights into JWTs. The FusionAuth Community Edition, a free authentication and authorization server, can also be a valuable tool in your technical arsenal. If you have any questions or require clarification, don’t hesitate to ask.

Additional Info: